The out-of-stock sticker shock we experienced in the past few years is forcing retailers to take a hard look at how they plan inventory.

Product availability was a clear problem during the pandemic: last holiday season, consumers saw over 6 billion out-of-stock messages online, a 253% increase over the 2019 season. Now, it’s been more than two years since we first heard the phrase “COVID-19,” and today’s state of inventory runs the gamut—some retailers are up to their ears (quite literally) with excess inventory while others are still waiting for restocks.

Why Has Inventory Been so Hard to Come By?

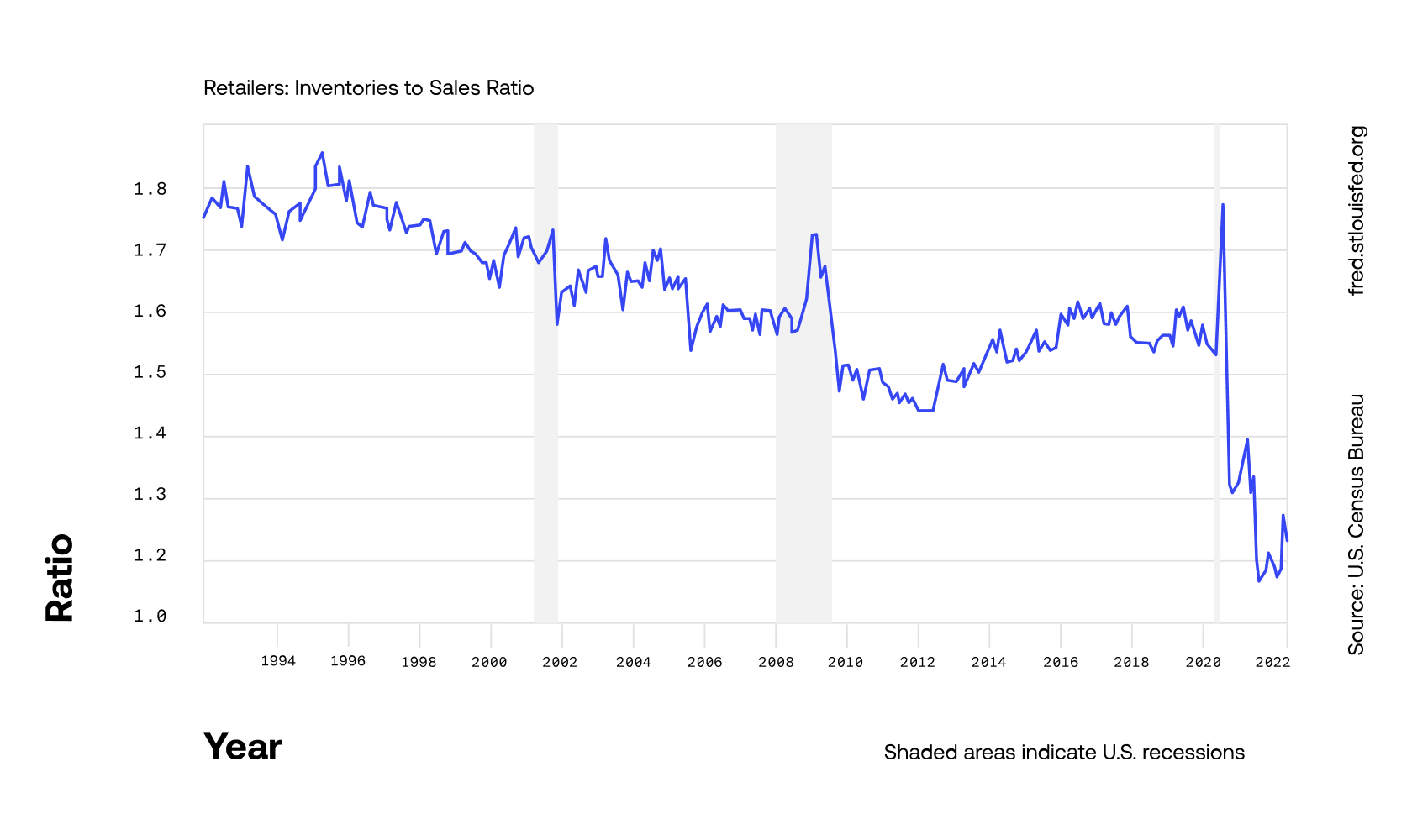

Near the start of the pandemic, the inventory-to-sales ratio in the U.S. plummeted—first down to 1.21 in July 2020 and bottoming out at 1.07 in April 2021. Meaning that, in April, retailers had enough inventory on hand to cover a mere 1.07 months of sales.

(Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data)

The reason for the lack of inventory is complex. First, the pandemic caused unforeseen changes in demand and labor challenges across the supply chain, leading to bottlenecks and disruptions that persist today. What’s more, many brands were not prepared to sell direct to consumer (DTC)—a trend that only accelerated during the pandemic. And, conversely, in-person shopping is once-again popular, causing DTC brands to diversify with B2B sales channels that bring greater complexities to their supply chain processes.

To top it off, while average inventory levels are still low, there are retailers at the opposite end of the spectrum today, struggling to find warehouse space for excess products. In part, because they have to—they’re finally receiving shipments and need to put them somewhere. For example, while consumer goods production recovered from international closures last summer, those goods would not reach the U.S. until after the holidays. Anecdotally, one brand recently sought storage space for more than 50,000 sq. ft. of excess inventory because their current warehouse simply didn’t have space for it.

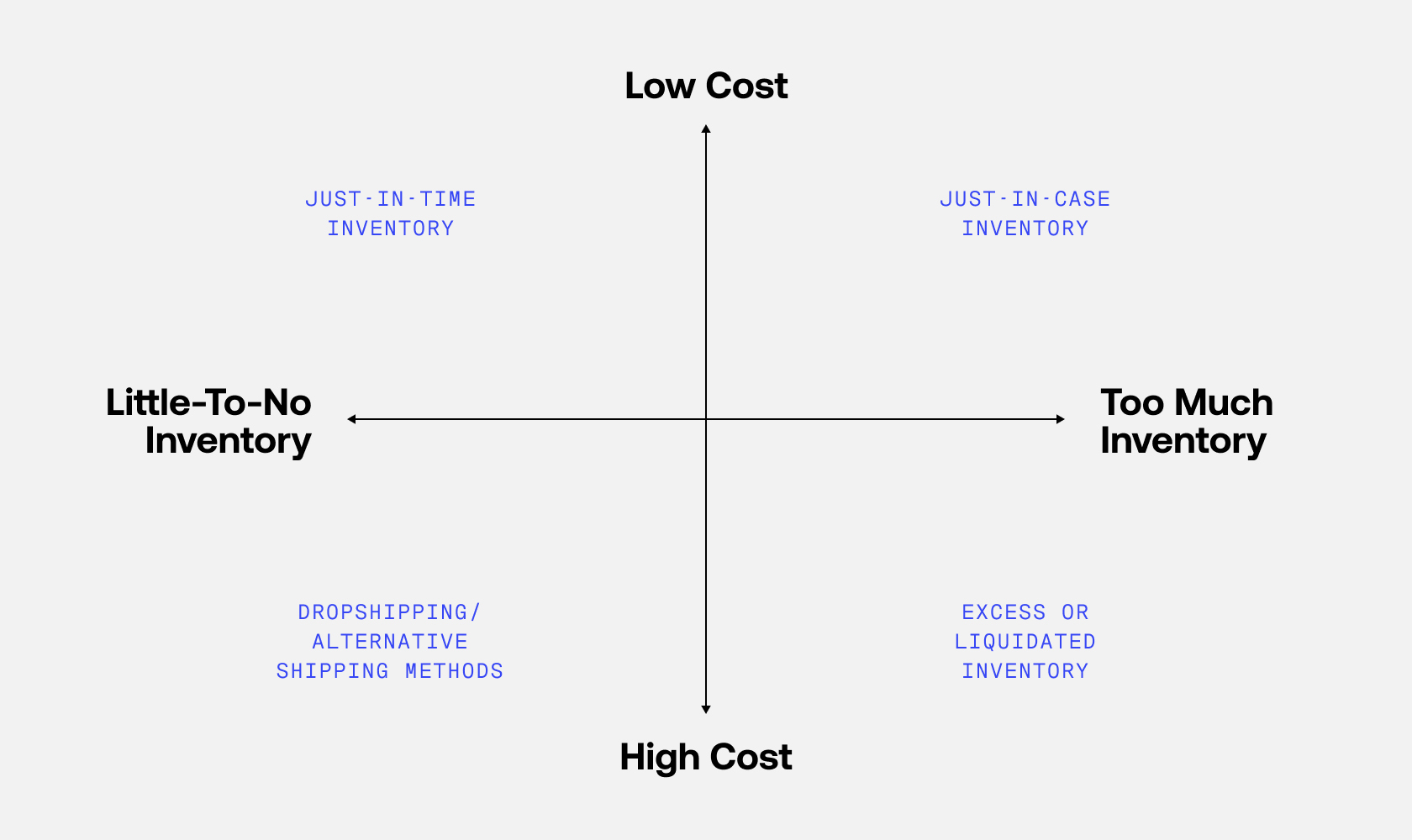

As sellers start to repair and rebuild their supply chain throughput, they need to ask themselves: what is that sweet spot for my own inventory levels? Do I stick with just-in-time inventory, and risk losing customers to out-of-stock messages, or do I add some cushion with just-in-case inventory, and stomach the extra costs that come with it?

Four Inventory Scenarios to Consider

Just-in-time Inventory

Let’s say a retailer wants just enough inventory on hand to cover this month’s demand. This approach would have an inventory-to-sales ratio of close to 1.0.

The benefits?

Less storage fees, since you don’t need to find a home for extra products—enough said.

Lower risk of having excess products that you simply can’t sell. This helps to avoid potential dilution of your brand, should items end up at discount chains, which luxury and exclusive brands especially want to avoid. Further, you’ll steer clear of having to liquidate any inventory, and any climate impacts that might have.

It takes less capital to purchase inventory, which helps to balance accounts for financially-tight retailers.

The risks?

Potential wasted spend on acquiring customers that are sent to out-of-stock product pages. Around 70% of consumers will switch retailers if they encounter out-of-stock items. Unless your marketing is in lockstep with your inventory levels, you risk paying to acquire customers that can’t buy.

You may lower the lifetime value of once-raving fans with a bad experience. Among loyal customers, 23% of them will quit their favorite brand should they experience slow or unreliable delivery.

Your overall revenue potential is limited when your inventory is smaller.

Global issues and supply chain disruptions will have a greater impact on your business, since you rely so heavily on those replenishments to keep your engine running.

Who should consider a just-in-time approach to stocking inventory?

Some industries are ideal for high inventory turnover ratios (a.k.a. just-in-time inventory). Grocery businesses are a prime example—they can’t stock expired tortillas or strawberries and expect to keep a customer base.

Like we mentioned above, brands that evoke a sense of exclusivity may benefit from low stock: luxury brands, custom sneaker collections, celebrity collaborations, etc.

If your product is unique with no major competition, you may be able to get away with storing less inventory. However, many unique direct-to-consumer (DTC) brands tend to live or die by their customer experience, which makes out-of-stock messages that much more terrifying.

Just-in-case Inventory

As you store more inventory domestically, your inventory-to-sales ratio goes up, which means you’re sitting on more product to sell.

The benefits?

An optimal customer experience, since you rarely have out-of-stock messages.

Potential manufacturing cost savings, since volumes are higher. (This may be offset if you have annual quotas or contract minimums with your manufacturers.)

Better equipped to scale and grow quickly, if consumer demand spikes.

The risks?

You may end up with product you can’t sell at full price at the end of a season, having to either mark down on your website, liquidate to a third party, or dispose and recycle.

There may not be room to store the extra inventory at your fulfillment centers. Make sure to check your contract(s) and chat with your vendors before ordering to make sure there’s a place to keep the pallets.

Who should consider a just-in-case approach to stocking inventory?

Naturally, if you’re expecting a spike in orders—maybe due to the upcoming holiday selling season or a TV appearance—you’ll want to pad your inventory levels.

Likewise, if you’re expecting hyper growth from your brand, possibly due to a new marketing initiative, investments, company forecasts, etc., then you’ll want to prepare for an increase in orders.

Consider the potential storage costs you may accrue if you increase your inventory. If your product is easily stackable, about the size of a shoebox, and comes in pallets that your warehouse operator can “set and forget”, your costs may be limited. Whereas, if your pallets are not stackable and large or bulky, you may have to pay a premium.

You’ll also want to think about the shelf life of your product(s). Does it have an expiration date? Is it seasonal or linked to hyperconsumerism (or fast consumerism) in some way? If you answered “no”, there’s less risk of ordering extra inventory, because you have a longer runway to sell your product.

Finally, for those brands with a wide range of SKUs, take a tiered approach to ordering inventory. You’ll likely have anchor products that drive the majority of sales. Make sure to have extra stock on hand for those main goods, and then consider ordering less of your other items.

Too Much and Too Little Inventory

It’s worth considering what happens at the extreme ends of the spectrum.

Too much inventory

Every company has a breaking point where it does not make sense to order more inventory because the supply significantly outweighs the demand. Some large brands bake this into part of their strategy, adding excess inventory as a line item in their budget and forecasting to help accommodate for unsellable goods. What they do with that product varies: they could store it, send it to a discount retailer, or liquidate it in another way.

Too little inventory

Prior to the pandemic, more and more retailers pushed the limit on the just-in-time inventory approach with zero or near-zero inventory on hand.

When you opt for a made-to-order process for manufacturing, you need to make sure you can get your items in a timely, cost-effective manner. If your manufacturer is overseas, for example, it may take weeks to months for the end consumer to receive their order. One-off purchases tend to be more costly, as well, which will eat into your bottom line.

It really boils down to the relationship with the manufacturer and the rest of the vendors in your supply chain. The further removed from the process and the smaller the scale, the greater the negative impact that supply chain disruptions and slowdowns will have on your business.

Examples: Inventory-to-sales Ratios by Industry

Consumer Packaged Goods (CPGs) / Food and Beverage Brands

To determine how much inventory a CPG retailer should stock, first let’s consider the type of product. Many of these goods—think staples like toilet paper, food, cosmetics, etc.—have high turnover rates, frequent and consistent purchase timelines, and may expire quickly.

Given these characteristics, it’s no surprise that the food and beverage industry has an incredibly low inventory-to-sales ratio of 0.70 (compared to 0.73 in January 2021). That means the inventory on hand won’t even fulfill a month’s worth of sales.

To be successful, these brands need to have tight supplier relationships in order to keep goods in stock at a frequent turnover rate.

Automotive

The car industry made headlines during the pandemic for its supply shortages. Unfortunately, the industry still hasn’t bounced back, with an inventory-to-sales ratio that’s lower in 2022 than 2021.

Last year, January 2021, motor vehicle and parts dealers had an inventory-to-sales ratio of 1.62, and this year, January 2022, the ratio is at 1.24.

It’s a fair prediction that this number will increase once the semiconductor shortage is over, but until then, expect disheartened consumers begrudgingly paying sky high prices for the little supply available.

Clothing

Clothing and clothing accessory stores tend to have a product that’s ideal for just-in-case inventory: the items are small, stackable, non-perishable, and the manufacturing costs are typically lower when purchased in higher quantities.

That said, clothing has a higher inventory-to-sales ratio than the others listed: 2.05 in January 2022 (compared to 2.24 in January 2021). This model can be replicated beyond clothing, if the products have a similar affinity for storing and selling longevity.

How to be More Efficient With the Inventory You Have

The good news? There are other levers to pull to increase efficiency without having to order more inventory.

First, make sure you have a clear, connected picture of your supply chain and the products within it. Avoid the manual labor that comes with analyzing and understanding disparate 3PL systems. Rather, find a solution that gives you full visibility into the entire supply chain, so you can make informed decisions about resupplying products.

Second, find a vendor partner that will help you be nimble with your inventory. Most brands are taking an omnichannel approach to selling: with DTC, B2B, and marketplace sales. For example, if a retailer sold via their own website, Target, and Amazon, each of those channels requires a different fulfillment strategy. Finding a warehouse vendor that supports all types of fulfillment will help the retailer move inventory between channels more quickly and efficiently, if needed.

As supply chains start to regain a more traditional throughput, retailers are going to have to make some tough decisions about their approach to inventory. The sweet spot is truly unique for each brand, and oftentimes one that changes with seasonality and global pressures.

So, which do you choose: just-in-time vs. just-in-case inventory? Well, you’ll likely have to dance a bit with both.